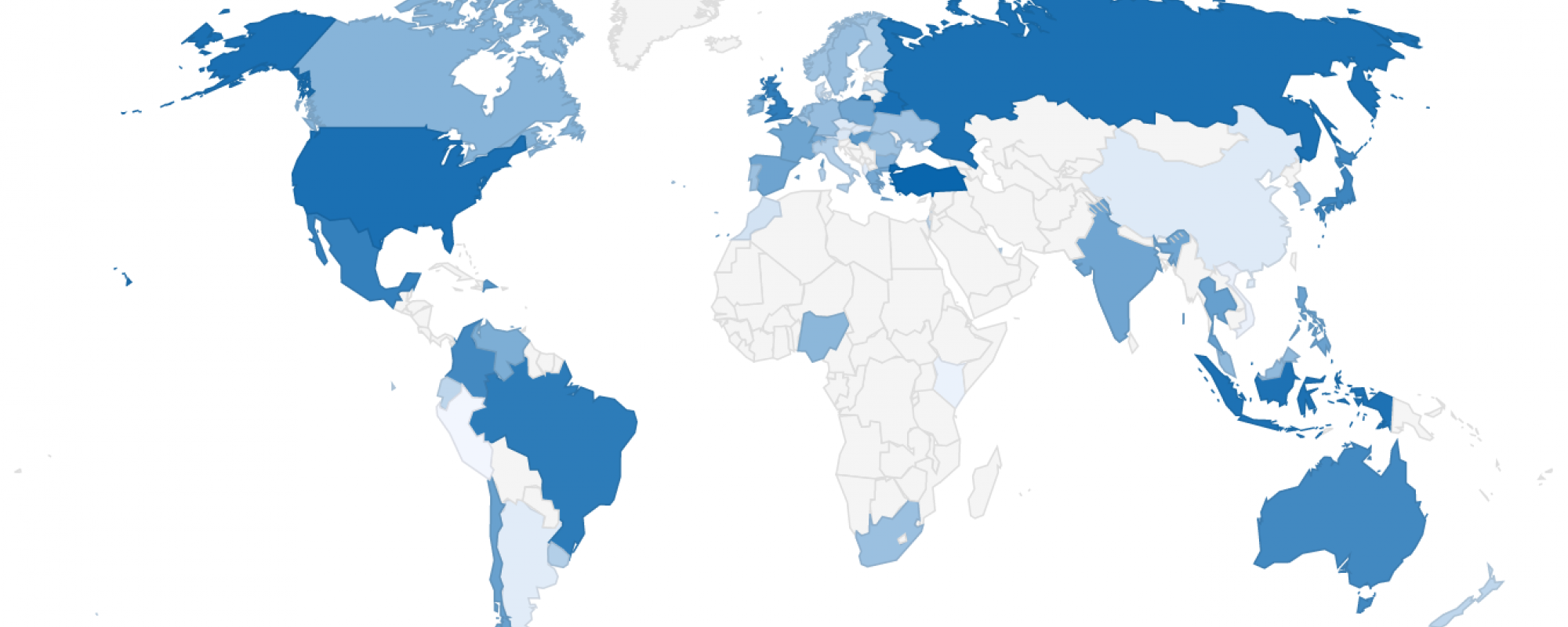

We conducted a large-scale survey covering 58 countries and over 100,000 respondents between late March and early April 2020 to study beliefs and attitudes towards citizens’ and governments’ responses at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Working paper is available here.

Note: data from this project is available here.

We conducted a large-scale survey covering 58 countries and over 100,000 respondents between late March and early April 2020 to study beliefs and attitudes towards citizens’ and governments’ responses at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Most respondents reported holding normative beliefs in support of COVID-19 containment measures, as well as high rates of adherence to these measures. They also believed that their government and their country’s citizens were not doing enough and underestimated the degree to which others in their country supported strong behavioural and policy responses to the pandemic. Normative beliefs were strongly associated with adherence, as well as beliefs about others’ and the government’s response. Lockdowns were associated with greater optimism about others’ and the government’s response, and improvements in measures of perceived mental well-being; these effects tended to be larger for those with stronger normative beliefs. Our findings highlight how social norms can arise quickly and effectively to support cooperation at a global scale.

We conducted a large-scale survey covering 58 countries, including many low- and middle-income countries at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic (between March 20th and April 7th, 2020). Participants were recruited globally through online snowball sampling and through media publications. In total 108,075 respondents responded to our survey during this period. This includes respondents from low- and middle-income countries such as Kenya, Vietnam, Indonesia, and India. In the survey we elicit perceptions of the behaviour of fellow citizens, governments, and respondents’ personality traits and mental well-being. To (partially) account for the selected nature of our sample we reweight our sample to be representative in terms of age, gender, income, and education.

We have four key findings.

First, respondents in our survey overwhelmingly reported adhering to a variety of COVID-19 containment measures, including avoiding social gatherings, washing hands more frequently, and staying home from work. Social norms appear to have played an important role in motivating this high level of adherence. In our survey, we asked individuals two sets of questions related to social norms. The first assessed their first-order injunctive beliefs–what they believed people should do–regarding eschewing social gatherings, avoiding handshakes, closing businesses, and stay-at-home orders. These questions were phrased , e.g., “What do you think: should people in your country cancel their participation at social gatherings because of the coronavirus right now?” The second set of questions assessed their second-order injunctive beliefs–what they believed others believed people should do. These questions were phrased e.g., “How many of 100 people in your country do you think believe that participation at social gatherings should be cancelled because of the coronavirus right now?” We find that participants report having very high first-order injunctive beliefs. For instance, over three-quarters reported believing that businesses should be closed. For other behaviours, injunctive beliefs were even higher. People’s second-order injunctive beliefs were, while lower than first-order beliefs, still high–always over 50%.

Second, if social norms indeed played a role in motivating adherence to COVID-19 containment measures, then we would make the following two predictions (Fehr and Fischbacher, 2004a; Bicchieri, 2005, 2016). First, first-order and second-order beliefs should be correlated with each other. Indeed, we find that they are correlated, r = .2. Second, these beliefs should be correlated with behaviour. Again, this is what we find. Both sets of beliefs were associated with adherence to containment measures, even in regressions that controlled for both at once. A one standard deviation increase in our first-order and second-order injunctive beliefs scales is associated with a 0.270 and 0.144 standard deviation increase in the likelihood of reporting compliance with at least one COVID-19 containment measure, respectively. These regress these two measures of mental well-being on variables that capture respondents’ views of their fellow citizens and government during the COVID-19 pandemic. Our analyses use country and date fixed effects, and control for baseline demographics as well as perceived and actual COVID-19 case prevalence. This means that the coefficient can be interpreted as the change in the dependent variable, in standard deviations of this variable, associated with an increase in the independent variable by one standard deviation.

Third, although respondents report high rates of adherence with containment measures themselves, nearly 60% report being dissatisfied with others’ adherence. They ex- press similar dissatisfaction with their governments’ response to the pandemic: only 9% of respondents report that their government’s response was too extreme. We find that those who had internalized social norms were most dissatisfied. A one standard deviation increase in our first-order injunctive beliefs scale was associated with a 0.078 and 0.101 standard deviation increase in reporting dissatisfaction with others’ response and the government, respectively.

Finally, we investigate the relationship between social norms and government responses on individuals’ reports of their mental well-being. Our survey included both a widely used depression scale known as the PHQ-8 (Kroenke et al., 2001), and a scale we developed to capture anxieties and worries specific to the COVID-19 pan demic, with items such as, “I am nervous when I think about current circumstances” and “I am worried about my health”. We correlate these scales with dissatisfaction of others’ responses, dissatisfaction with the government response, as well as measures of trust in government, and find that both measures of mental well-being are negatively correlated with dissatisfaction with others’ response, dissatisfaction with government response, and distrust of government. Changes in perceptions of others’ and the government’s response were strongest for those with higher first-order injunctive beliefs.