This study takes place in Nairobi, Kenya. It targets young jobseekers, with secondary education, who live in densely populated urban areas. Survey evidence indicates that African women in urban areas face large gender wage gaps and are underrepresented in better-paid occupations. Through surveys targeted at jobseekers, as well as firm managers, this study aims to understand the causes of occupational segregation and wage inequality by gender. In order to understand the extent to which lack of information leads to such labour market frictions, a random subsample of respondents will receive information about different sectors hiring practices and work attributes. The search behaviour and labour outcomes of the job applicants will then be analysed.

Gender gaps in labour force participation and earnings and high levels of occupational segregation by gender are pervasive in the developing world (e.g., Das and Kotikula, 2019). Women in Nairobi are less likely to be in formal wage work; are more likely to work in low-paid and low-progression sectors; and, conditional on being wage-employed, earn 83% of their male peers’ salary. A decomposition suggests that gender differences in industry and occupation account for roughly a third of this earnings gap (KCHS; Kenya National Bureau of Statistics, 2020). Gender gaps in labour market outcomes may arise due to demand-or supply-side factors. Employers may be less likely to hire female applicants or use screening practices that exclude women, such as hiring via referrals (Beaman et al., 2015). Female jobseekers may search differently: they may hold different beliefs about the labour market, sustained through gender-segregated networks, or prefer different jobs, due to expectations of future fertility, safety, or family preferences (McKelway 2023, Subramanian,2020).

The high degree of occupational segregation by gender in the Kenyan economy suggests the possibility of the misallocation of talent. If women sort into sectors that don’t let them exploit their comparative advantage, this will lead to aggregate productivity losses to the economy and harm to the individuals. Understanding and potentially intervening to target the key causes of occupational segregation for young adults has potentially large economic benefits: Young adults constitute a considerable share of the sub-Saharan African workforce and early sorting into occupations by gender may impede or enhance their development of occupation-specific human capital, with lifelong consequences for the job ladders they can access (Kambourov and Manovskii, 2009).

This research project will strive to answer some of the questions raised by these issues including:

1. (How) do employers treat women and men differently during hiring?

2. (How) do men’s and women’s preferences over job attributes, beliefs about the labour market, labour market choices, and search strategies differ?

3. (How) does providing accurate information to workers about the attributes the employers value and their recruitment strategies affect men’s and women’s search strategies

4. What portion of gender segregation and wage gaps can be accounted for by differences in jobseeker preferences, employer preferences, jobseeker misperceptions, and search strategies?

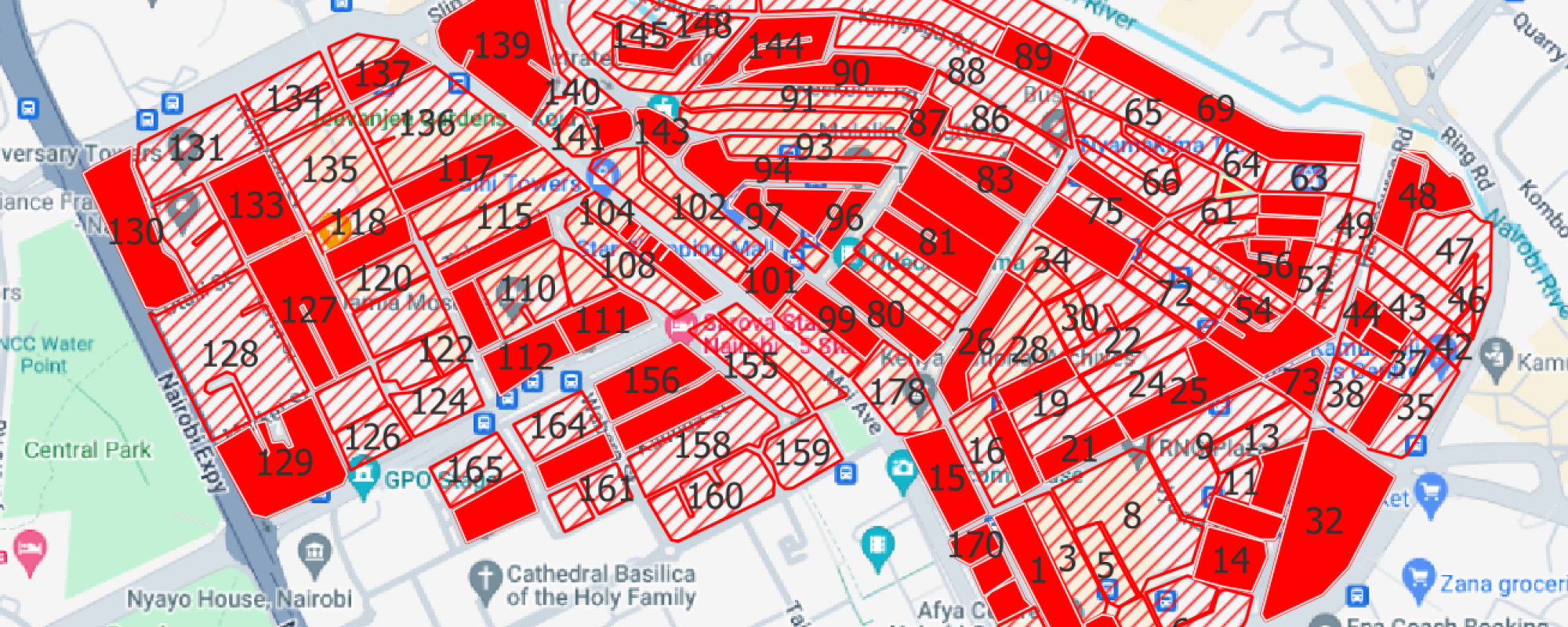

This project will focus on a sample of 1600 job-seekers across two settlements in Nairobi and a sample of 120 firms across 12 sectors.

(How) do employers treat women and men differently during hiring?

This question will be answered by surveying representatives of the 120 sampled firms. The respondents will assess hypothetical vignettes of jobseekers that will include typical information covered in a CV as well as contextual information, such as whether the applicant is a parent or whether they have a recommendation. This survey will be complemented by a hiring and employment practices survey that will collect factual information about hiring practices as well as current employment practices of the respondents, such as the wages they are setting for their employees, the roles, etc.

(How) do men’s and women’s preferences over job attributes, beliefs about the labour market, labour market choices, and search strategies differ?

Through a baseline survey, high-frequency phone survey, and endline survey, the researchers will elicit respondents’ preferences and beliefs about job attributes and beliefs, as well as their search behaviour.

(How) does providing accurate information to workers about the attributes the employers value and their recruitment strategies affect men’s and women’s search strategies?

In order to answer this question, a sub-sample of job-seekers will be randomly selected to be part of an information treatment. They will receive sector-level report cards with information about the level of experience and qualifications usually required by employers in that sector, as well as overall vacancies, and attributes associated with jobs in the field. The impact of this information treatment on search behaviour and outcomes will then be evaluated through a high-frequency panel.

What portion of gender segregation and wage gaps can be accounted for by differences in jobseeker preferences, employer preferences, jobseeker misperceptions, and search strategies?

To answer this question, researchers will estimate a dynamic model of workers’ search behaviour and occupational choice, which allows for rich preferences and potentially biased beliefs. This estimated model will allow researchers to explore channels that drive occupational segregation by gender and gender gaps that cannot be experimentally identified. The baseline worker survey will be used to identify workers’ beliefs about the labour market, returns to search, and unobserved job attributes. The discrete choice experiments embedded in the baseline survey will serve to identify workers’ preferences over job types. The firm survey will serve to similarly identify firms’ preferences for workers, the probability of obtaining a job in a given sector, workers' wage progressions, and the labour market risks of different job types. In addition, the variation induced by the experiment to identify parameters relating to the mapping between beliefs and search will also be exploited, as well as the mapping between job search and actual labour market outcomes. Finally, the high-frequency panel will allow us to identify how workers learn and update their beliefs throughout the search process (Conlon et al., 2018).