This study conducts a systematic review of the evidence on individual, family, community, and societal risk and protective factors for the mental health outcomes of children and adolescents who have been displaced to low-income and middle-income countries. The analysis aims to shed light on which individuals and groups are most likely to need intervention, and to identify which factors can be targeted by policies in the health, social, and immigration sectors.

What is the evidence on mental health outcomes of children who are forcibly displaced to low-income and middle-income countries? What are the risk factors that amplify the negative effects of displacement on mental health, and the protective factors that buffer the negative effects? What research and policy recommendations can be drawn?

Large numbers of children and adolescents are forced to migrate for a variety of reasons, ranging from armed conflict - which forcibly displaces an estimated 18 million children worldwide (UNCHR, 2009) - to natural disasters. The mental health of these children is of particular concern because of their experiences of insecurity at a formative stage of child development. The combined weight of socioeconomic adversity and exposure to violence in their countries of origin, followed by migration and the challenges of resettlement into a new context, exposes children to numerous risks to their physical, emotional, and social development. Risk factors affecting children’s mental health can be conceptualised as personal, social, and environmental factors that can adversely affect psychological and emotional development. Protective factors are associated with positive outcomes in the context of adversity, encompassing attributes of individuals’ social relationships and environments.

Despite low- and middle-income countries taking in most of the world’s refugees (UNDP, 2009) , research on mental health and forced displacement has focused on individuals who have resettled in high-income countries. Furthermore, the limited research covering low- and middle-income settings has focused mainly on assessing the prevalence of mental health disorders, and less on understanding risk and protective factors (Fazel et.al., 2005;). The present study focuses on the latter. The goals are twofold: 1) to shed light on which subgroups of children are likely to have higher risks to their healthy development and 2) to help identify effective ways to mitigate childhood vulnerabilities, strengthen positive attributes and foster psychosocial resilience in resource-scarce contexts.

This study conducts a two-part systematic review of the evidence on mental health outcomes and risk and protective factors in children who were forcibly displaced in low- and middle-income countries. The final sample of studies reviewed consists of 27 studies of forcibly displaced children from the following countries: Afghanistan, Bhutan, Bosnia, Cambodia, Democratic Republic of Congo, Kosovo, El Salvador, Eritrea, Guatemala, Iraq, Namibia, occupied Palestinian territory, Sudan, and Tibet, who were either internally displaced or resettled in Costa Rica, Honduras, India, Nepal, Nicaragua, Pakistan, Thailand, Turkey, and Uganda. Mental health outcomes measured in these studies were generally grouped as internalising or emotional problems, such as depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder; and externalising or behavioural problems.

-

Search criteria: The Medline, Scopus, PsycINFO, Embase, Web of Science citation, and Cochrane databases were systematically searched for studies about risk and protective factors that were reported from January, 1980, to July, 2010.

-

Inclusion criteria: Inclusion criteria were study population, publication date, data about risk and protective factors, and sample size. There were no language restrictions.

-

Sample criteria: a minimal sample size of 50 participants, and studies with 25 participants or more if a predictor variable was assessed for which there was minimum evidence from larger studies. Studies with participants up to and including the age of 18 years were eligible for inclusion; those with wider age categories were only included if all participants were younger than 25 years and mean age was 18 years or younger.

-

Country criteria: low- and middle-income countries as defined by the World Bank. The occupied Palestinian territory was included under middle-income countries according to its UN Development Programme classification.

-

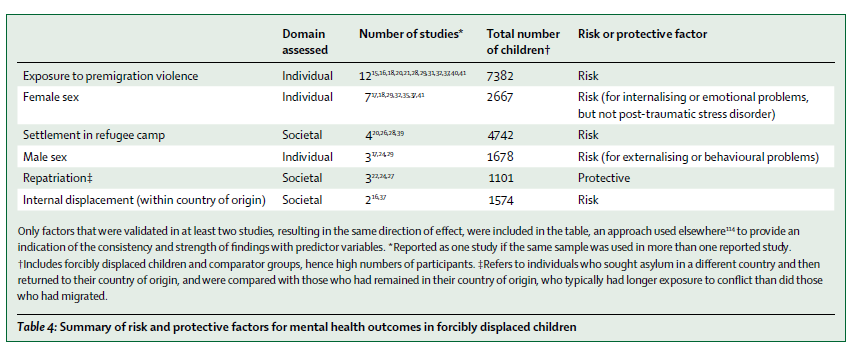

Despite the limited number of studies on the subject, the systematic review finds some patterns in protective and risk factors related to forced displacement and mental health outcomes (see table 4 below). Exposure to violence prior to migration is a significant risk factor that increases the likelihood of subsequent mental health problems. Some evidence also suggests that gender mediates the type of adverse effects on mental health; women are more likely to experience internalising or emotional problems, whereas men are more prone to suffer from behavioural or externalising disorders. Additionally, evidence suggests that the location into which refugees resettle is another important factor - settling in refugee camps is associated with a higher risk of mental health disturbances than settling in other types of locations. The evidence is fairly limited regarding protective factors, but some studies suggest that the mental health outcomes of refugees who are repatriated are similar or superior to the outcomes of individuals who did not migrate at all - potentially because those who migrated and then returned experience fewer adverse events than individuals who did not migrate.

The review makes several points regarding the direction of future research. First, it underscores the need to move from predictor variables at the individual level, such as exposure to violence or age, to a broader set of factors, including family, societal, premigration and postmigration factors. Second, it calls for a shift from simple cross-sectional analyses to longitudinal analysis that can better help establish causal pathways. Third, it calls for a move towards evaluating the effectiveness of different types of interventions. These interventions should be informed by systematic reviews of observational epidemiological studies, which so far seem to suggest that different types of adversities have different effects on mental health.

- UNHCR. Global report 2009. Geneva: UN High Commissioner for Refugees, 2010. http://www.unhcr.org/gr09/index.html (accessed March 18, 2011).

- Fazel M, Wheeler J, Danesh J. Prevalence of serious mental disorder in 7000 refugees resettled in western countries: a systematic review. Lancet 2005; 365: 1309–14.

- UNDP. Human development report 2009. Overcoming barriers: human mobility and development. New York: UN Development Programme, 2009.