This study shows that voters process information from pre-election polls using crude heuristics: they are overly swayed by whether a party is just winning a poll, compared to just losing. Using verified measures of voter turnout and self-reported and behavioural data, the experiment examines the effect of the different messages on voter turnout, vote choice and election and party beliefs. The results imply that the way the media frames poll results may have large effects on the outcome of elections.

Theory and lab experiments predict turnout is higher in competitive elections where votes are more pivotal, but are ambiguous on how pre-election polls in a close election affect voters. Most evidence on how information from polls affects voters’ behaviour, beliefs and voting decisions, assumes voters interpret information rationally, updating incorrect priors when they receive new information. However, behavioural economists and psychologists suggest acquiring and processing information consumes energy and time, so people use mental heuristics, or rules of thumb, to filter, categorise and interpret information. In a competitive election, this project tests these hypotheses, focusing in particular on whether voters swing behind the leading party (called a bandwagon effect) or the party that is behind (underdog effect).

The study is a field experiment conducted in the low-income, majority black African Soweto township in Johannesburg during South Africa’s 2016 municipal elections. This area votes predominantly for the African National Congress (ANC), which had been the incumbent government since the end of apartheid and the first democratic elections in 1994. As a result, before the 2016 election, the voters in this sample likely experienced the ANC as a dominant party government and continued to believe it was likely to win the city.

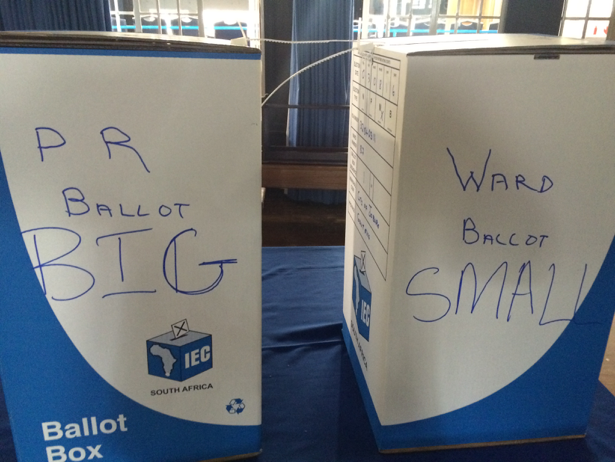

However, because of the electoral system and the way municipal boundaries are structured, city elections are much more competitive than national elections, and the 2016 election for the city of Johannesburg was particularly competitive. In the local elections, held every five years, the electoral system is a mixed member proportional system. Voters in Johannesburg and other metropolitan areas effectively cast votes in two elections. One vote is in the ward election to elect their ward councillor, decided on by a first-past-the-post system, among candidates from parties and independents. Wards have on average 16,592 registered voters in them in Johannesburg. Ward councillors convene meetings of residents, help residents to access services, and sit on the city council, where they make up half the council. The second election is for which party will run the city council and elect the mayor and cabinet. Voters get a second, “party” vote on a separate ballot for proportional representation (PR) seats, which make up the other half of the city council. Once the ward councillor seats have been allocated, the PR seats are allocated to parties so that each party’s share of seats in the council is proportional to its share of all votes cast (both ward votes and “party” votes).

The study takes place in Soweto, the largest and oldest township near Johannesburg, the country’s economic centre. Under apartheid’s residential segregation laws, city business districts and many suburbs were zoned for whites only. Black Africans were restricted to living in low-income urban areas near cities, known as townships, which typically consist of formal and informal housing and are located on the outskirts of cities. Soweto, a black African area, largely votes ANC. It is grouped into the City of Johannesburg with the largely white and ethnic minority suburbs of Johannesburg, which tend to vote for the opposition party, the Democratic Alliance (DA).

City elections had become progressively more competitive in the City of Johannesburg. The ANC won 59 percent of the combined ward and city council votes in 2011 (to the DA’s 34 percent) and 52 percent in the provincial ballot of the national elections in 2014 (to the DA’s 32 percent and the Economic Freedom Fighters’ 10 percent). In 2016, the ANC dropped a further seven points to 45 percent, while the DA picked up six to 38 percent and the EFF to 11 percent, enabling the two small parties to form a coalition. The DA and EFF picked up a large share of the votes in black African areas that had previously been won by the ANC. Turnout among black African voters in ANC-leaning areas dropped, and turnout in white suburbs increased dramatically.

The sample was a clustered convenience sample. The research team used 2011 Census data at small area level to identify electoral wards in Soweto, which are majority black African, lower-income and lower-literacy, and then randomly sampled among these wards. In each ward, central venues that enumerators could use for baseline surveys were identified. Most of the venues serve as community gathering points, libraries or recreational spaces, and are thus not associated with any particular political group. On each day of the baseline fieldwork, the team walked around an extended area surrounding that day’s venue to recruit subjects. Baseline fieldwork ran from 11 July 2016 to 26 July 2016, in a separate venue each day. Volunteers were screened to ensure they were South African citizens or permanent residents, over 18 and under 60, and registered to vote.

Once study respondents had been recruited, they completed a short baseline and were randomly assigned by the survey software to one of four groups; the control group, the placebo group and the two treatment groups. Treatment was delivered face-to-face with a get-out-the vote message, a short explanation of why the city council vote is important and information that the election would be close from a (poorly publicised) IPSOS-Mori poll. The first group were told the DA was just ahead of the ANC (by 3 points) and the second group that the ANC was just ahead of the DA (by 2 points). For each treatment group, respondents were shown a pie chart with the vote shares of each party as a visual aid. The placebo group got all of the information contained in the treatment messages, except for information from any polls or that the election was close.

Treatment and placebo groups received post-intervention reinforcement SMSs on 1, 2, and 3 August, in which their respective treatment texts were repeated. The municipal election in South Africa took place on 3 August 2016. Endline surveys began on 18 August and were completed by 25 October.

Researchers estimated two types of models: one looking at the overall effects of the two treatments and one looking at the treatment effects, conditional on partisanship. In particular, effects were examined on:

- ANC supporters hearing the ANC is just ahead of the DA (party they support is just winning)

- ANC supporters hearing the DA is just ahead of the ANC (party they support is just losing)

- DA supporters hearing the DA is just ahead of the ANC (party they support is just winning)

- DA supporters hearing the ANC is just ahead of the DA (party they support is just losing)

- Other voters hearing the incumbent, ANC, is just ahead

- Other voters hearing the challenger, DA, is just ahead

Researchers measured electoral outcomes – turnout and vote choice – and possible mechanisms – beliefs about party quality and beliefs about election outcomes.

Electoral outcomes:

For both ANC and DA partisans, there was a large and significant effect on turnout in the municipal election. Based on both self-reported and verified measures of turnout, it is possible to show that among ANC supporters who heard the ANC was just ahead in the polls, turnout rose by 7.5-8 percentage points (9.3-10.5%). Amongst DA supporters who heard the DA was just ahead, turnout rose by 23.5-24.6 points (38.9-40.8%). There were similar effects on vote choice, with baseline ANC (DA) supporters significantly more likely to report intending to vote for the ANC (DA). There were no effects on voters who found out their party was just behind (underdog effects).

Mechanisms:

The voters who learned their party was just winning, rather than just losing, rated the quality of that party and its leader more highly. They were also more likely to believe the party would win a higher share of the vote. These differences arose in spite of receiving no new information about the party’s quality – only the information from one poll.

Ballot boxes in the city election.