This RCT addresses informal, network-based hiring techniques in Ethiopia through an information intervention (psychometric testing) and by subsidising formal vacancy posting.

Highs levels of urban youth unemployment and a disproportionately large number of small firms with informal, network-based hiring processes are common characteristics of developing economies (World Bank, 2018; ILO, 2016). This is not different in Ethiopia, where unemployment levels are particularly high for urban youth living in geographically remote areas of town (Franklin, 2018) and young people with high school education (Abebe et al., 2019). Disadvantaged job-seekers, who lack credible signals of their ability, such as women (Abel et al., 2019; Beaman et al., 2018) or minorities (Witte, 2019), often struggle to access the existing opportunities. Even though Ethiopia has experienced an average economic growth rate of 10% in the past 15 years, the country still faces the challenge of bringing large sections of its growing population into gainful employment.

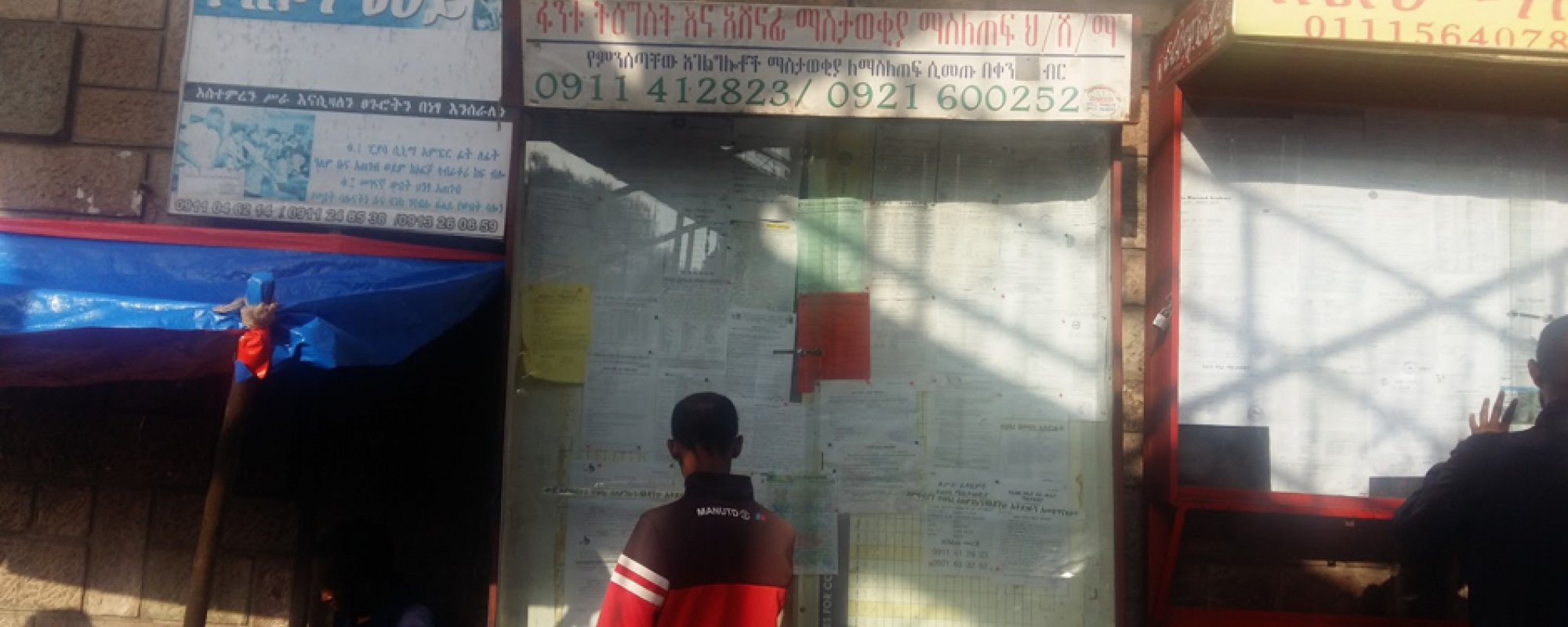

This experiment is set in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, which is a relevant setting to study how firms’ hiring processes affect firm-level outcomes. The average quality of matches made in Addis Ababa’s labour market is low, a problem common to many developing country labour markets. This is reflected in average yearly turnover rates of about 30% of the workforce for SMEs in the Addis Ababa Firm Survey. In line with this evidence, a majority of SMEs in the same survey report high worker turnover as their most important labour management problem. High turnover could be caused by both behavioural biases and market imperfections. The surveyed SMEs further mention unmotivated workers as the second most important problem, while the lack of technical skills (which are easier to observe) is listed less frequently. The fact that firms list worker qualities that are particularly difficult to observe during the application process as problematic points to substantial information frictions. Firms partially overcome these frictions by hiring through networks of existing employees. However, the reseearcgers hypothesize that firms’ reliance on network-based hiring techniques might also be part of managers’ reluctance to experiment with new search methods (Chandrasekhar et al., 2020).

From previous research conducted by the investigators, we know that Ethiopian firms, particularly in the manufacturing and service sector, struggle i) filling existing vacancies with adequate candidates and ii) coping with high employee turnover. This points to a matching problem between the supply and demand side of the urban Ethiopian labour market. A number of recent studies looked at potential labour supply side constraints causing this mismatch: information asymmetries (e.g. about work-seeker abilities (Abebe et al., 2019), or spatial barriers to employment (such as costs of public transport for job-search or commuting (Franklin, 2018)). On the other hand, labour demand side constraints as well as the interaction of labour demand and supply are relatively understudied in this context. This project tries to fill this gap, with a particular focus on how SMEs in Addis Ababa can increase hiring and firm performance by switching to formal hiring channels. Informal hiring practices might affect small and medium enterprises’ (SME) ability to hire productive employees, ultimately impeding business performance and growth. Addressing firms' hiring practices in this context is of particular importance, as several previous studies have emphasised the importance of referral networks in particular for Ethiopian urban labour market outcomes (Serneels (2007); Witte (2019)). By investigating ways of improving the quality of job matches and, thus, worker productivity in firms, we expect to boost firm-level productivity and growth of SMEs.

More generally, there is a growing amount of evidence that management practices matter for firm performance and explain a substantial amount of the difference in GDP between poor and rich countries (Bloom et al., 2010). The intervention used in this study has the aim of improving firms' management practice on one specific dimension - the hiring process - which should contribute to decrease differences in overall management quality and, thus, firm productivity.

Beyond labour-market frictions, there could also be a fundamental mismatch of work-seekers’ skills and firms’ demand for specific skills. However, there is scant systematic knowledge as to which skills are demanded, leaving policy makers and youths guessing how to set their education priorities. The researchers will provide unique data on firms’ demand for specific skills that Ethiopia’s education policy makers can use to identify and address skill-mismatches and gaps.

This experiment will address the main factors that lead to firms in low- and middle-income countries relying on informal, network-based hiring techniques. First, researchers will reduce firms’ reliance on information about candidates obtained through informal hiring channels (e.g. referrals), researchers will experimentally improve firms’ candidate screening technology by pre-screening applicants with psychometrically validated measures and by passing this information on to participating firms. This is based on the observation that network-based hiring techniques often provide firms with information about applicants that they cannot obtain through formal channels (e.g. Dustman et al., 2016), and that applicants cannot signal through standard education or training certificates. Second, to increase the value of the improved screening technology for firms, researchers encourage firms to increase their applicant pool by posting formal vacancies. Researchers will do this by reducing firms’ vacancy posting costs through targeted subsidies. They divide 625 small and medium-sized firms into two treatment groups and a control group which will not receive any treatment. The first treatment group will only receive the vacancy subsidies while the second treatment group will receive the vacancy subsidies and the opportunity to have all applicants to their vacancies screened in our screening centre.

This study has four key findings. First, while the intervention successfully increases formal vacancy posting in treated firms, we do not observe an average increase in the total number of vacancies created. Treated firms are 3.3 times and statistically significantly more likely than control firms to post at least one vacancy through formal search channels. However, there is no significant difference between treatment and control firms in terms of vacancy creation. Instead, we observe a significant reduction in the fraction of filled vacancies by 20 percentage points.

The second finding further explains why treated firms struggle to fill vacancies. We find that treated firms are a significant 5.6 percentage points more likely to create at least one white-collar vacancy. This is an increase of 81 percent relative to the control group mean. Additionally, both the overall number of white-collar vacancies and the share of white-collar postings among all vacancies increase by approximately 40 percent compared to control firms. This increase in white-collar vacancies does not lead to an increase in white-collar hires, which instead remain constant, with point estimates close to zero.

Our third finding speaks to how incomplete information about applicant skills might prevent formal employee search. We randomly offer half of the treated firms the option of having all applicants to their vacancies screened for three cognitive or socio-emotional skills, on top of the vacancy posting subsidy. This add-on treatment does not impact the uptake of the intervention, vacancy creation, or hiring outcomes, suggesting that information frictions about applicants’ skills are not driving low levels of formal employee search.

Finally, we show that some treatment effects persist beyond the treatment period. On the one hand, we find that once the vacancy subsidy runs out, treated firms do not continue posting job adverts in formal channels. How- ever, on the other hand, we observe a persistent shift from non-white-collar vacancy creation to white-collar vacancies.

Abebe, G., Caria, S., Fafchamps, M., Falco, P., Franklin, S., & Quinn, S. (2019). Anonymity or Distance? Job Search and Labour Market Exclusion in a Growing African City. Working Paper.

Abel, M., Burger, R., & Piraino, P. (2019). The Value of Reference Letters -Experimental Evidence from South Africa. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, forthcoming.

Beaman, L., Keleher, N., & Magruder, J. (2018). Do Job Networks Disadvantage Women? Evidence from a Recruitment Experiment in Malawi. Journal of Labor Economics, 36(1), 121--157.

Bloom, N., Mahajan, A., McKenzie, D., & Roberts, J. (2010). Why Do Firms in Developing Countries Have Low Productivity? The American Economic Review, 100(2), 619–623.

Dustmann, C., Glitz, A., Schönberg, U., & Brücker, H. (2016). Referral-based job search networks. Review of Economic Studies, 83(2), 514–546.

Franklin, S (2018) . Location, Search Costs and Youth Unemployment: Experimental Evidence from Transport Subsidies. Economic Journal 128 (614), 2353-2379.

ILO (2016). World Employment and Social Outlook: Trends 2016. International Labour Office – Geneva

Serneels, P. (2007). The nature of unemployment among young men in Urban Ethiopia. Review of Development Economics, 11(1), 170–186.

Witte, M. (2019). Job Referrals and Strategic Network Formation: Experimental Evidence From Urban Neighbourhoods in Ethiopia, Working Paper.

WorldBank (2018). World Development Report 2018: Learning to Realize Education's Promise. Washington, DC: WorldBank.