This study investigates how a large, one-off cash transfer from an NGO to the poorest 40% of households in 1,030 villages in Western Kenya impacts civic engagement and community behaviour. We conduct post-treatment surveys of households, local leaders and local elected politicians. This enables us to explore how these groups respond to the income shock in terms of their civic behaviour, engagement in the local community and participation in democratic processes and how interactions between these communities and local leaders are affected.

- How does a short-term spike in income affect community engagement? Do cash villages become more or less active in tackling community matters?

- Do interactions between local politicians and households change as a result of the reduction in poverty? Are recipient households and villages requesting more service provision, private support or public goods from local authorities? Do officials change their behaviour towards communities or households due to the transfers?

- Do cash recipients dedicate more time to democratic processes, such as voting in elections and attending candidate hustings? Are they better informed about local politics, or feel more empowered to make a change through their choice of candidate?

Many theories in political science argue that increases in income improve citizen engagement, the extent to which citizens demand services and hold politicians accountable, and the overall levels and quality of service delivery (Lipset, 1959; Inglehart and Welzel, 2005). However, there is limited causal evidence on the effect of changes in income on civic engagement and interactions with the state. Most sources of exogenous variation in income, such as cash transfers, are delivered by governments. The effects of these transfers capture two theoretically distinct processes: changes in perceptions, attitudes and values as income increases, and changes in perceptions of a state which successfully delivers a programme (Larreguy, Marshall, and Trucco, 2015). The design of this study enables us to disentangle these two dimensions, focusing on income shifts alone. Moreover, the transfers in this study are considerably larger than those typically delivered by governments and NGOs, which means we observe the impact of a meaningful shift of the local income distribution.

The setting of this study is particularly well-suited to research on the impact of rising incomes on interactions between citizens and local officials. The devolution of power and resources to 42 county governments in Kenya in 2010 increased the level of funding allocated locally and created real opportunities for households and communities to petition their leaders. For example, Ward Development Funds were established to enable the Members of County Assembly (MCA) to provide resources targeted at the main issues in their areas. By law, MCAs must hold consultation meetings in each sublocation in their ward before they can finalise the allocation of funding between projects. This governance structure provides households with genuine opportunities for interaction with their leaders and enables communities to petition for services. Therefore, this setting enables us to observe how such interactions are affected by changes in the local income distribution.

In addition, relatively free and transparent elections offer citizens the chance to hold local officials accountable in the ballot. A general election was held just before this study began, in August 2017. This timing enables us to observe the effects of cash transfers on participation in democratic processes, such as campaigning on behalf of local candidates, attending hustings to learn about candidate quality, and voting. The ability to observe whether these processes change as a result of cash transfers means we can evaluate the relationship between rising incomes and democratic participation, without the usual endogeneity concerns associated with government-led programmes.

Finally, the study has implications for any interventions (governmental or external) which provide income support to poor communities. There are many existing processes and institutions through which individuals or communities can receive support. One example is the widely-held, informal fundraising meetings (harambees), which raise money for a range of causes, from supplies for school children to a family’s funeral expenses. Community groups (chamas) are another form of participation, these range from savings and table-banking organisations to business associations. This study provides crucial evidence on how these existing, often informal arrangements and institutions are affected by shifts in community-level income distributions, and whether participation in such institutions changes for recipient households.

This study combines two existing trials evaluating the socio-economic impact of a cash transfer programme delivered by GiveDirectly in Western Kenya. The first trial, “General Equilibrium Effects of Cash Transfers in Kenya” by Egger et al (2019) takes place in 650 villages in the northern part of Siaya County. The transfers, which came to $1,871 PPP, were rolled out between September 2014 to August 2015 and payments were made in two lump sums, six months apart. The second trial, “Promoting Future Orientation Among Cash Transfer Recipients” by Orkin et al (2019), has a sample of 410 villages spread over two counties - southern Siaya and Homa Bay. Transfers of $2,237 PPP were rolled out in two lump-sum payments, two months apart, between November 2016 and June 2017.

In both trials transfers were randomly assigned to half of the villages and the cash was delivered through a mobile money service (m-Pesa). Households had to meet pre-specified, observable criteria to be eligible for transfers, such as having a mud floor or having no telephone, and approximately 40% of households were eligible.

Data for this study comes from surveys conducted after treatment with 10,084 households and local leaders: 1,095 Village Elders (village-level representatives), 113 Assistant Chiefs (sublocation-level representatives) and 72 candidates for the post of Member of County Assembly (lowest-level elected officials). We look at the difference between treated and untreated individuals to analyse changes to a range of outcomes, at three levels of analysis:

|

Ward-level |

Village-level |

Household level |

|

MCA behaviour

|

Civic participation

|

Civic participation

|

|

MCA election race outcomes

|

Requests for Outside Resources

|

Democratic participation

|

|

Mobilisation of funding

|

Interactions between households and local leaders

|

We highlight the following key findings for discussion.

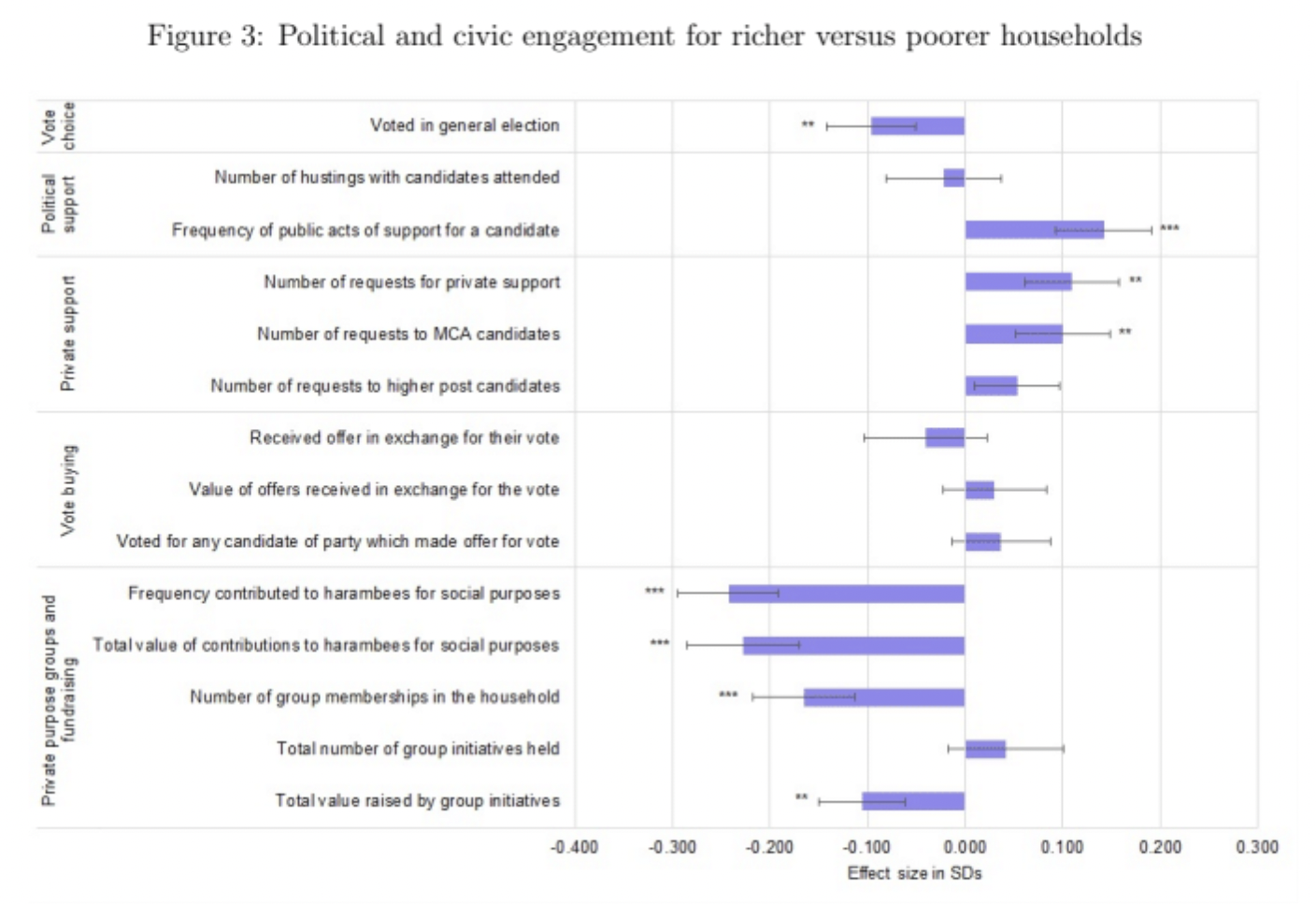

For many of our measures of civic and political engagement, we observe differences according to whether the household was eligible to receive the cash transfer.

At the ballot box, receiving a cash transfer does not affect turnout and, overall, there is only mild evidence that the cash transfer affects "formal" political engagement through channels such as voter turnout. Evidence is mixed. Household survey data suggests that eligible households, in placebo villages, are slightly less likely (2%) to turn out to vote than ineligible households. However, administrative data from polling stations suggests a higher intensity of cash transfers into a village does not translate to increased turnout.

Observed differences, by household eligibility, are largely found in more informal forms of political or civic engagement.

- Households who have received a cash transfer decrease private exchanges of patronage with politicians: attending fewer rallies (for which they receive small payments), making fewer requests for private support and receiving fewer offers to sell votes. However, ineligible households in cash villages increase such exchanges.

- The prevalence of group-based civic participation increases in cash villages. Informal committees (harambees) are more common for school fees, funeral expenses, collections for orphans and hospital bills. The total amount raised for these causes also increases.

- We argue this suggests cash enables households to shift out of “subsistence” political engagement into higher value group engagement with group fundraisers raising significantly more than private requests.

Lipset, S. M. (1959). Some Social Requisites of Democracy: Economic Development and Political Legitimacy. American Political Science Review, 53(1), 69–105.

Inglehart, R., and Welzel, C. (2005). Modernization, Cultural Change, and Democracy: The Human Development Sequence. Cambridge University Press: New York.

Larreguy, H., Marshall, J., and Trucco, L. (2015). Breaking Clientelism or Rewarding Incumbents? Evidence from an Urban Titling Program in Mexico. Harvard University Working Paper, 1–63.

Egger, D., Haushofer, J., Miguel, E., Niehaus, P., and Walker, M. W. (2019). General Equilibrium Effects of Cash Transfers: Experimental Evidence from Kenya. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper, no. 26600, 1–53.

Orkin, K., Garlick, R., Mahmud, M., Sedlmayr, R., Haushofer, J., and Dercon, S. (2019). Direct and Interaction Effects of Cash Transfers and Psychological Interventions Promoting Future Orientation on Economic Outcomes: Analysis Plan. AEA Trial Registry, 996.